Dr. Michael Newman, DNM, Ph.D, HHP, FAIS.

September 24, 2024

What Are Staghorn Kidney Stones? (Symptoms, Causes, and Treatment)

This site contains product affiliate links. We may receive a commission if you make a purchase after clicking on one of these links

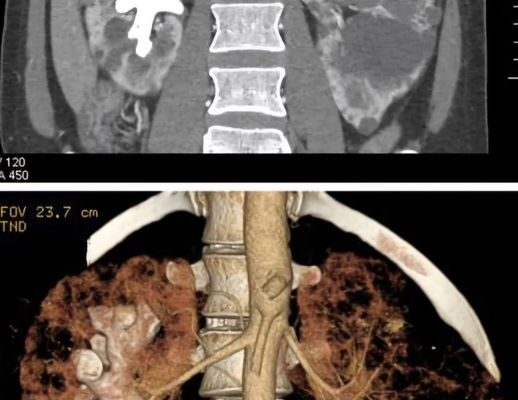

Staghorn stones are large, branching kidney stones that can wholly or partially fill the renal pelvis and calyces (Healy & Ogan, 2007). They are typically found on one side of the body and are less common in men (Diri & Diri, 2018) (Johnson et al., 1979). Staghorn stones are linked with urinary tract infections (UTIs) caused by urease-producing bacteria, leading to rocks known as struvite infection stones (Torricelli & Monga, 2020a).

There are 4 Kidney Stone Types: Calcium oxalate, Uric acid, Struvite, and Cystine.

1. Calcium Oxalate

Calcium oxalate crystals are the most prevalent type of crystal found in urine and are a leading cause of kidney stones. When there is an excess of oxalate, it can bind with calcium to create kidney stones and crystals. These formations can inflict harm on the kidneys and impede their function. Remarkably, approximately 80% of kidney stones are comprised of calcium; of that 80%, about 80% are classified as calcium oxalate stones (Finkielstein, 2006a).

2. Uric Acid

Hyperuricemia, a high uric acid level in the bloodstream, can be caused by an overproduction of uric acid, reduced excretion, or a combination of both factors. If left unmanaged, this condition can form urate crystals, resulting in the painful condition known as gout. Moreover, high levels of uric acid, even without crystal formation, have been associated with severe health conditions such as hypertension, atherosclerosis, insulin resistance, and diabetes (Soltani et al., 2013). Understanding these potential risks can motivate individuals to take preventive measures against hyperuricemia.

Uric acid is a byproduct of dissolved purines, natural compounds in the body and certain foods and beverages. Foods high in purine include liver, anchovies, mackerel, dried beans and peas, and beer. When these purine-rich foods are consumed, the body breaks down the purines into uric acid, resulting in an elevated uric acid level in the bloodstream (So & Thorens, 2010).

3. Cystine

Excessive levels of cystine in the urine can result in the development of kidney stones, which have the potential to become stuck in the kidneys, bladder, or urinary tract. Individuals diagnosed with cystinuria frequently experience repeated occurrences of kidney stones (Shen et al., 2017). While the condition can be well-managed, there is currently no known cure. Cystine, a naturally occurring chemical compound, can crystallize in the urine, forming kidney stones (Moussa et al., 2020).

4. Struvite Stones

Struvite urinary stones, also known as “infection stones” or “triple phosphate” stones, are typically caused by infections in the upper urinary tract. These complex structures form from chemicals in the urine. Once they develop, the kidney can retain or pass the stone along the urinary tract and into the ureter (Griffith, 1978).

Read More: Vitamin D Overconsumption Leaves Man With Permanent Kidney Damage

Staghorn Kidney Stone Symptoms and Conventional Treatment

If a staghorn calculus is present in your kidney, you may notice symptoms such as a fever, pain on the side between your ribs and hip, and blood in your urine (hematuria). These kidney stones can result in various manifestations, including pain in the abdomen, side, groin, or back and blood in the urine (Mayo Clinic, n.d.).

The treatment of staghorn calculus typically involves surgical intervention to remove the stone, including any small pieces, to prevent infection or the development of new stones. One effective method for eliminating staghorn stones is percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL), the gold standard surgical treatment for staghorn renal stones, particularly those larger than 2.0cm in size (De et al., 2015) (Torricelli & Monga, 2020b).

Dietary Management and Supplementation Modification

In the 1940s, a low-phosphate and calcium diet was proposed to reduce the risk of developing staghorn stones (Shorr, 1950).

In 1968, the role of dietary advice in inhibiting staghorn stone formation was studied. Those who followed the dietary regimen reported a marked decline in stone recurrence following the nephrolithotomy procedure (Lavengood & Marshall, 1972).

1. Fluid Intake

The foundation of effective management is centred around increasing urine volume. Research suggests that this impact follows a linear trend, with a point of diminishing return observed when urine volumes exceed 2.5 litres per day. According to recommendations, consuming 2.5 to 3 litres of fluid daily is advised to achieve this goal (Finkielstein, 2006b).

2. Calcium Supplement with Meals

When taking calcium carbonate supplements with meals, oxalate excretion in the urine is reduced, which benefits individuals at risk of developing stones. On the other hand, taking these supplements at bedtime increases the excretion of calcium in the urine. It does not significantly impact oxalate excretion (Domrongkitchaiporn et al., 2004). For those prone to stone formation (Finkielstein, 2006a), it is preferable to use calcium citrate as a supplement, as it increases urinary citrate excretion. If it is challenging to increase dietary calcium, a recommended dose of 200–400 mg is suggested.

Read More: Risk Factors & Early Warning Signs of Chronic Kidney Disease

3. Remember: Limit Foods High in Oxalate.

Oxalates are natural compounds that are present in a wide range of foods. Some familiar sources of oxalates include green leafy vegetables (such as spinach and kale), starchy vegetables (like potatoes and beets), fruits, nuts (especially almonds), cereal grains, soy, and tea (Han et al., 2015). When consumed, oxalates are processed by the body and are naturally produced as waste products. It’s essential to limit the consumption of foods high in oxalate. You can reduce their impact by consuming them with extra fluids and including dietary sources of calcium to lower oxalate absorption (Garland et al., 2020) (Finkielstein, 2006b).

4. Vitamin C (ascorbic acid)

Additionally, vitamin C can convert to oxalate, so taking vitamin C (ascorbic acid) supplements may increase oxaluria (oxalates in urine) and be linked to a higher risk of stone formation. As a result, it’s recommended to limit vitamin C supplements to less than 1000 mg per day (Curhan et al., 1996) (Finkielstein, 2006a).

5. Remember to Regulate Your Consumption of Animal-based Protein.

A diet that includes an excessive amount of animal protein can contribute to kidney stone formation. It is advised to control the intake of animal-based protein obtained from sources such as beef, pork, poultry, or fish daily. Research indicates that a diet high in animal protein, due to purines, can produce uric acid during metabolic processes, potentially elevating the likelihood of uric acid stone development (Curhan & Taylor, 2008) (Kenny & Goldfarb, 2010).

6. Monitor Your Sodium Intake

Excess salt in the diet can lead to increased calcium excretion by the kidneys, raising the risk of developing kidney stones. Monitoring sodium intake can be achieved by carefully reading food labels to identify high-sodium products. Additionally, it is essential to consider adjusting calcium supplementation, as it can impact the formation of calcium oxalate stones (Chung, 2017) (Afsar et al., 2016).

7. Omega-3 (EPA) Has Some Potential Benefits

Omega-3 fatty acids, known as PUFA, found in oily fish such as mackerel, salmon, and albacore tuna, have numerous health benefits. However, current evidence regarding their impact on kidney stones is limited. While there isn’t strong evidence from the general population about the role of PUFA in preventing kidney stone formation, studies on dietary interventions suggest that fish oil or supplemental EPA can reduce the excretion of certain substances in the urine, thus lowering the risk of stone formation. Based on these trial results, fish oil is the most effective supplement despite the wide range of conditions in which the trials were carried out. Fish oil helps reduce calcium excretion in patients who form stones, lowering the risk of further stones. It is recommended that fish oil be used as a supplement to treat these patients. This emphasizes the need for more research to define fish oil’s potential benefits in this area (Rodgers & Siener, 2020).

Conclusion

Staghorn renal stones, or struvite stones, are large kidney stones that fill the renal pelvis and at least one renal calyx. They are typically composed of magnesium ammonium phosphate. They are associated with recurrent urinary tract infections caused by urease-producing pathogens.

In developing countries, around 10 to 15% of all urinary stones are struvite stones, and women are affected more frequently than men. However, in developed countries, the incidence of renal stones is lower due to early diagnosis and management (Flannigan et al., 2014). Staghorn renal stones carry a significant morbidity and potential mortality rate of approximately 30%, making prompt assessment and active surgical management essential (Teichman et al., 1995) (Gao et al., 2020).

Taking a holistic approach to managing staghorn renal stones involves being mindful of the foods consumed, stress levels, fluid intake, and other lifestyle factors. These include limiting green leafy vegetables, starchy vegetables, fruits, nuts, cereal grains, soy, chocolate, and tea, being cautious with calcium timing and vitamin C supplements, regulating animal-based protein and salt intake, and considering the potential benefits of omega-3 (EPA) supplementation.

Moreover, untreated staghorn stones can block the calyces in the kidneys, leading to caliectasis, which, if not treated, can result in kidney failure. Therefore, seeking timely medical attention and treatment for staghorn renal stones is crucial to prevent complications.

Disclaimer: This information is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment and is for information only. Always seek the advice of your physician or another qualified health provider with any questions about your medical condition and/or current medication. Do not disregard professional medical advice or delay seeking advice or treatment because of something you have read here.

Read More: 10 Common Habits That May Harm Your Kidneys

Sources

- Afsar, B., Kiremit, M. C., Sag, A. A., Tarim, K., Acar, O., Esen, T., Solak, Y., Covic, A., & Kanbay, M. (2016). The role of sodium intake in nephrolithiasis: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and future directions. European Journal of Internal Medicine, 35, 16–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2016.07.001

- Chung, M. (2017). Urolithiasis and nephrolithiasis. JAAPA, 30(9), 49–50. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.jaa.0000522145.52305.aa

- Curhan, G. C., Willett, W. C., Rimm, E. B., & Stampfer, M. J. (1996). A prospective study of the intake of vitamins C and B6, and the risk of kidney stones in men. The Journal of urology, 155(6), 1847–1851. Retrieved September 13, 2024, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8618271/

- Curhan, G., & Taylor, E. (2008). 24-h uric acid excretion and the risk of kidney stones. Kidney International, 73(4), 489–496. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ki.5002708

- De, S., Autorino, R., Kim, F. J., Zargar, H., Laydner, H., Balsamo, R., Torricelli, F. C., Di Palma, C., Molina, W. R., Monga, M., & De Sio, M. (2015). Percutaneous nephrolithotomy versus retrograde intrarenal surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Urology, 67(1), 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2014.07.003

- Diri, A., & Diri, B. (2018). Management of staghorn renal stones. Renal Failure, 40(1), 357–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886022x.2018.1459306

- Domrongkitchaiporn, S., Sopassathit, W., Stitchantrakul, W., Prapaipanich, S., Ingsathit, A., & Rajatanavin, R. (2004). Schedule of taking calcium supplement and the risk of nephrolithiasis. Kidney International, 65(5), 1835–1841. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00587.x

- Finkielstein, V. A. (2006a). Strategies for preventing calcium oxalate stones. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 174(10), 1407–1409. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.051517

- Finkielstein, V. A. (2006b). Strategies for preventing calcium oxalate stones. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 174(10), 1407–1409. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.051517

- Flannigan, R., Choy, W., Chew, B., & Lange, D. (2014). Renal struvite stones—pathogenesis, microbiology, and management strategies. Nature Reviews Urology, 11(6), 333–341. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrurol.2014.99

- Gao, X., Fang, Z., Lu, C., Shen, R., Dong, H., & Sun, Y. (2020). Management of staghorn stones in special situations. Asian Journal of Urology, 7(2), 130–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajur.2019.12.014

- Garland, V., Herlitz, L., & Regunathan-Shenk, R. (2020). Diet-induced oxalate nephropathy from excessive nut and seed consumption. BMJ Case Reports, 13(11), e237212. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2020-237212

- Griffith, D. P. (1978). Struvite stones. Kidney International, 13(5), 372–382. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.1978.55

- Han, H., Segal, A. M., Seifter, J. L., & Dwyer, J. T. (2015). Nutritional management of kidney stones (nephrolithiasis). Clinical Nutrition Research, 4(3), 137. https://doi.org/10.7762/cnr.2015.4.3.137

- Healy, K. A., & Ogan, K. (2007). Pathophysiology and management of infectious staghorn calculi. Urologic Clinics of North America, 34(3), 363–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ucl.2007.05.006

- Johnson, C. M., Wilson, D. M., O’Fallon, W. M., Malek, R. S., & Kurland, L. T. (1979). Renal stone epidemiology: A 25-year study in rochester, minnesota. Kidney International, 16(5), 624–631. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.1979.173

- Kenny, J.-E. S., & Goldfarb, D. S. (2010). Update on the pathophysiology and management of uric acid renal stones. Current Rheumatology Reports, 12(2), 125–129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-010-0089-y

- Lavengood, R. W., & Marshall, V. F. (1972). The prevention of renal phosphatic calculi in the presence of infection by the shorr regimen. Journal of Urology, 108(3), 368–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-5347(17)60743-2

- Mayo Clinic. (n.d.). Diseases & conditions [Kidney stones]. mayoclinic.org. Retrieved September 10, 2024, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/kidney-stones/symptoms-causes/syc-20355755

- Moussa, M., Papatsoris, A. G., Abou Chakra, M., & Moussa, Y. (2020). Update on cystine stones: Current and future concepts in treatment. Intractable & Rare Diseases Research, 9(2), 71–78. https://doi.org/10.5582/irdr.2020.03006

- Rodgers, A. L., & Siener, R. (2020). The efficacy of polyunsaturated fatty acids as protectors against calcium oxalate renal stone formation: A review. Nutrients, 12(4), 1069. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12041069

- Shen, L., Cong, X., Zhang, X., Wang, N., Zhou, P., Xu, Y., Zhu, Q., & Gu, X. (2017). Clinical and genetic characterization of chinese pediatric cystine stone patients. Journal of Pediatric Urology, 13(6), 629.e1–629.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpurol.2017.05.021

- Shorr, E. (1950). Aluminum gels in the management of renal phosphatic calculi. Journal of the American Medical Association, 144(18), 1549. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1950.02920180013005

- So, A., & Thorens, B. (2010). Uric acid transport and disease. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 120(6), 1791–1799. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci42344

- Soltani, Z., Rasheed, K., Kapusta, D. R., & Reisin, E. (2013). Potential role of uric acid in metabolic syndrome, hypertension, kidney injury, and cardiovascular diseases: Is it time for reappraisal? Current Hypertension Reports, 15(3), 175–181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-013-0344-5

- Teichman, J. M., Long, R. D., & Hulbert, J. C. (1995). Long-term renal fate and prognosis after staghorn calculus management. Journal of Urology, 153(5), 1403–1407. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-5347(01)67413-5

- Torricelli, F. M., & Monga, M. (2020a). Staghorn renal stones: What the urologist needs to know. International braz j urol, 46(6), 927–933. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1677-5538.ibju.2020.99.07Torricelli, F. M., & Monga, M. (2020b). Staghorn renal stones: What the urologist needs to know. International braz j urol, 46(6), 927–933. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1677-5538.ibju.2020.99.07

Disclaimer: This information is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment and is for information only. Always seek the advice of your physician or another qualified health provider with any questions about your medical condition and/or current medication. Do not disregard professional medical advice or delay seeking advice or treatment because of something you have read here.